As a rookie Haskeller coming from imperative languages I am still

often shocked how elegantly mathematical problems can be expressed in this

great language. Last time a wrote a blogpost about recursion.

As an example, I presented the

Relation type and implemented an operation to it I called join. If you are

familiar with relational algebra you might have recognized that this is a

specific case of equijoin,

where you join pairs so that the first pair’s second element matches the second

pair’s first element.

I was thinking about a more complex problem I could solve with this toolkit, one

that is understood by most programmers and challenging as well. Slowly I pieced

together that the problem of finding shortest paths in directed graphs fits

quite naturally into our existing picture.

“How are relations and joins relate to finding shortest paths in graphs the first place?” one might wonder. To find the answer, let’s look at this definition of graphs:

a set of vertices V

a set of edges E, E subset of VxV

a graph G, G(V,E)

This fits directed graphs without parallel edges. If parallel edges were allowed,

VxV would not be a set. If edges were undirected, that would mean that (v1, v2)

is the same as (v2, v1), which would require as to alter our definition of AxA.

Luckily directed graphs without parallel edges perfectly suffice for the most

scenarios when you want to find shortest paths, so we can stick by them.

With above constraints, graphs can be represented with a relation that has the same codomain as its domain, where items in the relation are edges in the directed graph. We have to make one modification though: let’s assign numbers to the edges, in order to represent a cost attribute associated with the given edge.

Now that we have a basic understanding of the problem domain, let’s see how our

existing toolkit (the Relation example code from the last post) can help us:

import Data.List (union)

data Rel a b = Rel [(a, b)] deriving Show

-- union of two relations

(\/) :: (Eq a, Eq b) => Rel a b -> Rel a b -> Rel a b

(\/) (Rel rs) (Rel qs) = Rel $ union rs qs

-- equijoin two compatible relations

(|><|) :: (Eq a, Eq b, Eq c) => Rel a b -> Rel b c -> Rel a c

(|><|) (Rel rs) (Rel []) = Rel []

(|><|) (Rel []) (Rel qs) = Rel []

(|><|) (Rel ((r0, r1):rs)) (Rel ((q0, q1):qs)) =

let

match = if r1 == q0

then Rel [(r0, q1)]

else Rel []

leftHead = Rel [(r0, r1)]

leftTail = Rel rs

right = Rel $ (q0, q1):qs

rightTail = Rel qs

in

match \/ (leftHead |><| rightTail) \/ (leftTail |><| right)

Note: I realized that the symbol & is not well suited for

join, so I changed to |><|, which resembles the bowtie symbol used for equijoin

in relational algebra textbooks.

What can we reuse from this?

The most apparent change we need make is to the definition of the Rel term

constructor so it can represent the cost attribute associated with each item in

the relation. Adding a Float should be enough. I name the inner structure

unRel for convenient extracting that will come in handy later.

data Rel a b = Rel { unRel :: [((a, b), Float)] } deriving Show

Note that the distinct type variable b for items in the codomain is unnecessary

for graphs (why?), but this more general definition hopefully will not do any harm.

Now, you will see compilation errors in |><|, which requires us to rewrite it

according to our new Rel definition. How would you rewrite it? Let’s take a

second and look at it.

The recognition is that we can use a specialized version of |><| to sum costs

along paths. The general structure of the algorithm as well as the match criterion

is unaffected, the only thing we need is to sum the costs upon a match.

Here is the rewritten operation:

(|><|) :: (Eq a, Eq b, Eq c) => Rel a b -> Rel b c -> Rel a c

(|><|) (Rel rs) (Rel []) = Rel []

(|><|) (Rel []) (Rel qs) = Rel []

(|><|) (Rel (((r0, r1), cr):rs)) (Rel (((q0, q1), cq):qs)) =

let

match = if r1 == q0

then Rel [((r0, q1), cr + cq)]

else Rel []

leftHead = Rel [((r0, r1), cr)]

leftTail = Rel rs

right = Rel $ ((q0, q1), cq):qs

rightTail = Rel qs

in

match \/ (leftHead |><| rightTail) \/ (leftTail |><| right)

This way, we can iteratively assign costs to paths:

- start out with edges

- in each iteration:

- join the edges with themselves

- union this with the previous set keeping only minimums for each distinct

(a, b)edge

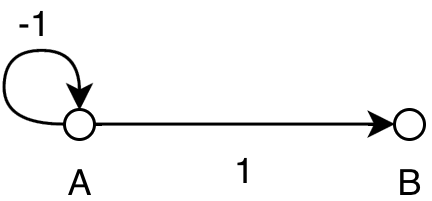

When does this iteration terminate? Possibly never as shown below:

0: (a, a, -1), (a, b, 1)

1: (a, a, -2), (a, b, 0)

2: (a, a, -3), (a, b, -1)

...

n: (a, a, -n - 1), (a, b, 1 - n)

The reason is clear: if we have a negative circle, we can include it to

our path as many times we want to make the overall path less costly. The simplest

thing to do in order to give an upper bound however, is to limit it to the number

of edges minus one. Why? If there are no negative loops then an optimal path

contains each edge at most once, and a path with length of n can be assembled

with n - 1 iterations, which means that we will find all the optimal paths without

negative loops this way. For the negative loop containing paths however the number will

be still smaller than in any of the previous iterations.

How do we filter out the shortest paths?

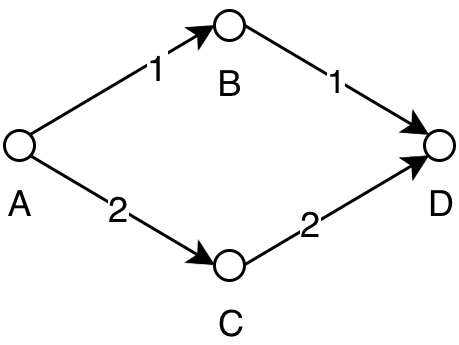

0: (a, b, 1) (a, c, 2) (b, d, 1) (c, d, 2)

1: (a, b, 1) (a, c, 2) (b, d, 1) (c, d, 2) (a, d, 2)

...

3: (a, b, 1) (a, c, 2) (b, d, 1) (c, d, 2) (a, d, 2)

If you try to visualize the algorithm in your head, you can see that in the second

iteration two paths from a to d are competing, but only the one through b

should be added to the result set, because that is the shortest. This means after

applying the union we either need to further filter shortest paths or modify the

union function to do this. I do the first, it’s easier this way.

-- custom comparator that only cares about the edges

sameEdge :: (Eq a, Eq b) => ((a, b), Float) -> ((a, b), Float) -> Bool

sameEdge ((y0, y1), cy) ((x0, x1), cx) = y0 == x0 && y1 == x1

-- first, sort the array so the same paths get next to each other (we

-- need the Ord typeclass for both of our type variables).

-- Group the result so that the same paths go into the same group.

-- Get the head of every group. The result will be the shortest of each the paths

-- with the same start and end

filterMinCost :: (Ord a, Eq a, Ord b, Eq b) => [((a, b), Float)] -> [((a, b), Float)]

filterMinCost = map head . groupBy sameEdge . sort

All we have to do now is write the actual iteration! Your turn, scroll up a little to the algorithm’s summary and try to implement it according to it. It’s kind of easy now that all the dirty work is taken care of.

The implementation is:

shortestPathsRec :: (Ord a, Eq a) => Int -> Rel a a -> Rel a a

shortestPathsRec 0 r = r

shortestPathsRec n r =

let

previousPaths = shortestPathsRec (n - 1) r

in

Rel $ filterMinCost $ unRel $ previousPaths \/ (previousPaths |><| previousPaths)

shortestPaths :: (Ord a, Eq a) => Rel a a -> Rel a a

shortestPaths x = shortestPathsRec (length (unRel x) - 1) x

Let’s try it on the above examples to see if it works:

repl> let g = Rel [(('a', 'b'), 1), (('a', 'c'), 2), (('b', 'd'), 1), (('c', 'd'), 2)]

repl> shortestPaths g

Rel {unRel = [(('a','b'),1.0),(('a','c'),2.0),(('a','d'),2.0),(('b','d'),1.0),(('c','d'),2.0)]}

Nice! Let’s see the quirky negative loop:

repl> let h = Rel [(('a', 'a'), -1), (('a', 'b'), 1)]

Rel {unRel = [(('a','a'),-2.0),(('a','b'),0.0)]}

Both works as expected, so it seems that the implementation is okay. However, if happen to find an error please point it out to me please. 🙂

Where to go from here?

Well, in computational sense, this algorithm is far from optimal. At least applying merge the filter with the union would eliminate a fold and I think even more complexity can be spared by going with Floyd’s algorithm instead. Challenge: try implementing it functionally!

In code quality sense, the cost attribute surely could be refactored into something

more general. The cost calculation intruding our otherwise pretty generic |><| also

smells of bad design.

Thanks for reading,

have a wonderful day!